April 1990

This is the text of the article I sent to MacTutor magazine in October 1989. They published this in their April 1990 issue. I recovered the text in March 2025 from an ancient Microsoft Word for Macintosh file using LibreOffice, which can miraculously open up these old files when other applications cannot.

I have cleaned up the source code a bit for the sake of readability, now that I don’t have to pack the code into a magazine column or view it on a nine-inch screen. I got rid of some of my idiosyncracies in my original code, such as wrapping the body of each switch case in brackets; this was unnecessary, and I was pretty new to C at the time.

You might notice the odd combination of K&R C-style function definitions and C89-style function prototypes. In K&R C, the parameter lists after the function names contain the parameter names without types, but the parameter names and types are given in a separate list before the function’s opening curly brace. C compilers at the time were changing to support to the ANSI/ISO 1989 C standard, so things were in flux.

You might also notice that I mention creating a project file with the suffix “[pi symbol],” (changed here in the source code because at the moment my process for generating PDF files from Markdown source chokes on pi symbols). It was fairly common on old MacOS to use symbols in filenames. In this case, my convention was to use a pi symbol to indicate a THINK C or Pascal project file. The actual file types in old MacOS were part of the file metadata and independent of the file names, an innovation designed to improve the user experience.

A few months ago I was developing a program that used a modal dialog. I showed the results to my roommate. He ran the program and brought up the dialog, but was then interrupted. When he got back, the screen saver had come on. He moved the mouse to refresh the screen, and then scrutinized my display.

“Which button is default?” he asked.

“That one. The program drew the outline, but it got erased.”

“It should be there.”

“Oh, come on! The Finder doesn’t even keep the outline around its default buttons when you use a screen saver!”

“If it’s in Inside Macintosh, it should be there. Go fix it. Here, make me a copy first.” He popped in a blank disk. Nothing happened.

“How come it didn’t ask if I want to initialize the disk?”

“That doesn’t work when a modal dialog is active,” I explained lamely.

He then pressed the “Q” key. Nothing happened. “There’s a dialog button called Quit — why didn’t it quit?” he asked. “What kind of user-friendly program is this, anyway?”

My roommate was right. We are used to putting up with the limitations of modal dialogs, but the ModalDialog toolbox call can be extended using filter procedures. The parameters of ModalDialog can be declared in C as follows:

void ModalDialog (filterProc, itemHit)

ProcPtr filterProc;

int *itemHit;The address of your filter procedure gets passed by casting it to a procPtr. If you don’t want to use a filterProc, you pass NIL as your first parameter. If you do use a filterProc, ModalDialog then gets each event for you, using a mask which excludes disk events, and sends them to your filterProc. It is then up to your filterProc to decide what to do with them. ModalDialog expects your filterProc to be declared as follows:

pascal Boolean FProc(Dialog, Event, itemHit)

DialogPtr theDialog;

EventRecord *theEvent;

int *itemHit;A dialog filterProc is actually a function that returns a Boolean value. This value should be TRUE if you want ModalDialog to exit, and FALSE otherwise. ModalDialog passes your filterProc a pointer to the current event. You then can do what you want with it. If your function returns FALSE, ModalDialog will handle the event after you. Thus, you can get a crack at each event even before ModalDialog does. Your filterProc can then do any of the following:

My filterProc uses the first technique to handle updateEvents before ModalDialog gets them. This allows me to redraw the default box around a button and then tell ModalDialog to do its own updating. I use the second technique to exit ModalDialog if my filterProc receives a key event that it understands. I use the third technique to handle the <return> key by changing the event from a keypress to a click in the default button. You don’t actually have to do this for <enter> and <return> keypresses, since ModalDialog handles key events, but I wanted to illustrate the technique of altering an event.

Scott Knaster, in Macintosh Programming Secrets, suggests that command-key equivalents be provided for buttons in modal dialog boxes whenever possible. Command-key equivalents aren’t always necessary, however. Some popular applications, such as Microsoft Word, provide single-key equivalents for button clicks, if no editable text fields are present in the dialog, such as in the Save Changes Before Closing dialog. I suggest that command-key equivalents be used in modal dialogs with editable text fields, and single-key equivalents (or both single-key and command-key equivalents) be used when no editable text fields are present. My code illustrates both techniques, but your application should use only one. Even though my modal dialog has an editable text field, I allows the user to press a 1, 2, or 3 to choose one of my three buttons. The user can also use <command>-F, S, and T to choose the first, second, and third dialog items, respectively. NOTE: You must make certain that the editText item(s) in the DITL resource that you use are set to Disabled, or else my technique will not work.

When drawing your dialogs with ResEdit, keep in mind that the command-key character is ASCII 17 in the Chicago font, but cannot be typed directly from the keyboard. Microsoft Word will generate this character if you use the Change function to replace a specified character with a ^17. You can then copy this character and paste it into your ResEdit fields. RMaker can generate this character by using \11.

Since ModalDialog does not pass disk events to the filterProc, I use the fourth technique to allow the user to insert a blank disk while the ModalDialog call is active. It gets initialized by DIBadMount, which then mounts it (or ejects it, if initialization failed). This might be useful in a modal dialog which displays on-line volumes. SFPutFile uses this technique to allow disks to be mounted while its dialog is active.

There are other ways you can handle events in a modal dialog using filterProcs. You can do anything you want during null events. You can plot a series of icons in your dialog to give the appearance of animation, or draw the current time using DrawString. After all, you have the current grafPort, and can draw directly with QuickDraw. Remember, though, that your drawing operations should be as fast as possible, and must take much less than a single tick to work effectively. Also, remember your poor end-user: don’t make your dialogs overly confusing or complex. We want to extend the Macintosh interface, not bury it.

If you like my code, you are welcome to use it “as-is,” modify it, or completely rewrite it. I’d appreciate it if you’d put my name somewhere in your application, but you can drop me a postcard instead.

/* This Think C 3.02/4.0 code should be compiled

with MacHeaders turned on. Create a new

project called FilterProc.[pi symbol], and

add this file, driveDialog.c, along with

HandleDialog.c and MacTraps. Prototypes

are provided. Compile the resource file,

FilterProc.r, with RMaker and put it in the

folder with the FilterProc project. */

/*********************************************/

/* File: driveDialog.c */

/* A simple driver application for the dialog

handler. Your own application would call

it instead. */

void main (void);

int HandleDialog(short ID);

void main()

{

int itemHit, /* Dialog item hit, returned by HandleDialog */

counter;

InitGraf(&thePort);

InitFonts();

InitWindows();

InitMenus();

TEInit();

InitDialogs(0L);

FlushEvents(everyEvent, 0);

InitCursor();

/* Now send the HandleDialog function the resource ID

of the DLOG to use */

itemHit = HandleDialog ((short)1);

/* Now beep to tell us what item number the HandleDialog call

sent back (i.e., what item was hit to exit ModalDialog) */

for (counter = 1; counter<= itemHit; counter++)

SysBeep(40);

}/*****************************************/

/* File HandleDialog.c */

/*****************************************/

/* Prototypes */

int HandleDialog(short Dialog_ID);

/* Called whenever you want to put up a modal dialog */

pascal Boolean FProc(DialogPtr theDialog,

EventRecord *theEvent,

int *itemHit);

/* Filter procedure called by ModalDialog to screen dialog

events */

Point CenterDialogItem(DialogPtr theDialog, int item_number);

/* Returns the center of the rect of a dialog item,

to be called from a filter proc while a modal dialog is

active. */

void FlashDialogItem(DialogPtr theDialog, int item_number);

/* Flashes an item of a dialog, to be called from a filter

proc while a modal dialog is active. */

void HandleUpdate(DialogPtr theDialog);

/* Used to handle update events while a modal

dialog is active, called from a filter proc.*/

/************************************************/

/* This procedure returns the center of a dialog item as a

point. It is designed to be used with buttons, but will

work with any type of dialog item. */

/* Input: theDialog (a DialogPtr), item number (an integer) */

/* Output: a point */

Point CenterDialogItem(theDialog, item_number)

DialogPtr theDialog;

int item_number;

{

Point the_center; /* Center of item, to return */

int itemType; /* Returned by GetDItem but not used */

Handle theItem; /* Returned by GetDItem but not used */

Rect the_Rect; /* Returned by GetDItem */

GetDItem(theDialog, item_number, &itemType, &theItem,

&the_Rect);

the_center.h = the_Rect.left +

((the_Rect.right - the_Rect.left) / 2);

the_center.v = the_Rect.top +

((the_Rect.bottom - the_Rect.top) / 2);

return the_center;

}

/************************************************/

/* This procedure flashes an item of a dialog */

/* Input: theDialog (a DialogPtr), item_number (an integer) */

/* Output: none */

void FlashDialogItem(theDialog, item_number)

DialogPtr theDialog;

int item_number;

{

long tickScratch; /* returned by Delay, unused */

int itemType; /* Returned by GetDItem but not used */

Handle the_item; /* Handle to the item */

Rect controlRect; /* Returned by GetDItem but not used */

GetDItem(theDialog, item_number, &itemType, &the_item,

&controlRect);

HiliteControl(the_item, 1);

Delay(6, &tickScratch);

}

/************************************************/

/* The following function handles update events for your dialog box.

It is called whenever the filterProc receives an update event.

You can put whatever you want to be drawn in the dialog in it.

Right now it redraws the rounded rect around the default button

(number one). */

/* Constants for drawing roundRect */

#define edgeCurve 16

#define gapBetween -4

#define lineSize 3

void HandleUpdate(theDialog)

DialogPtr theDialog;

{

Rect controlRect; /* rectangle of the default control. We

need this to draw the round rect. */

int itemType; /* Returned by GetDItem but not used */

Handle the_item; /* ditto */

Rect border; /* Rect of the thick border */

PenSize(lineSize, lineSize);

/* Get control #1's rectangle and grow it a little bit,

then call FrameRoundRect to draw it. */

GetDItem(theDialog, (int)1, &itemType, &the_item,

&controlRect);

border = controlRect;

InsetRect(&border, gapBetween, gapBetween);

FrameRoundRect(&border, edgeCurve, edgeCurve);

}

/************************************************/

/* The following filterProc is used to handle extra

events during the modal dialog loop, such as update

events. Its original purpose was to keep the

default round-rect drawn around the control even

after a screen saver has redrawn the screen. It

also handles insertion of blank disks and

button-keyboard equivalents.

NOTE: If you have one or more editable text fields

within your modal dialog, your key equivalents should

use the command key. If you don't have any editable

text fields, your key equivalents can be handled

straight. The names of your buttons should all begin

with unique first letters, and if you use command-key

entry you should provide a legend of command-key

equivalents next to the buttons. */

pascal Boolean FProc(theDialog, theEvent, itemHit)

DialogPtr theDialog;

EventRecord *theEvent;

int *itemHit;

{

long key; /* Holds the key code */

Point ctr; /* where the mouse click will go */

int DIResult; /* Returned by DIBadMount */

EventRecord diskEvent; /* Returned by EventAvail, below */

/* Since ModalDialog doesn't handle bad disk mounts, we

have a handler that will allow the user to format new

disks with a modal dialog still on the screen. */

if (GetNextEvent(diskMask, &diskEvent) == TRUE)

{

if (HiWord(diskEvent.message) != 0)

{

diskEvent.where.h =

((screenBits.bounds.right -

screenBits.bounds.left)

/ 2) - (304 / 2);

diskEvent.where.v =

((screenBits.bounds.bottom -

screenBits.bounds.top)

/ 3) - (104 / 2);

InitCursor();

DIResult = DIBadMount(diskEvent.where,

diskEvent.message);

}

} /* end of if GetNextEvent test for disk events */

switch (theEvent->what)

{

case (updateEvt):

/* Do not return an item hit value. Returning FALSE tells

ModalDialog to handle the update event. We have just

added our own handling of the event. */

HandleUpdate(theDialog);

return FALSE;

break;

case (keyDown):

key = theEvent->message & charCodeMask;

switch(key)

{

/* If a key has been pressed, we want to interpret

it properly. */

case 13: /* Return key */

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 1);

ctr = CenterDialogItem(theDialog, 1);

/* We can do it this way: change the event

record to fool ModalDialog. ModalDialog

doesn't flash the button long enough for

my taste, so I flash it some more myself. */

theEvent->what = mouseDown;

LocalToGlobal (&ctr);

theEvent->where = ctr;

theEvent->message = 0;

/* Now we tell ModalDialog to handle the

event. It doesn't suspect a thing! */

*itemHit = 1;

return FALSE;

break;

case 3: /* the Enter key */

/* Or we can do it our own way by flashing

the button and telling ModalDialog to exit. */

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 1);

*itemHit = 1;

return TRUE;

break;

/* These key equivalents do not rely on the use of

the command key. You would use these in your modal

dialog only if you had no editable text fields. */

case 49: /* 1 key */

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 1);

*itemHit = 1;

return TRUE;

break;

}

case 50: /* 2 key */

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 2);

*itemHit = 2;

return TRUE;

break;

}

case 51: /* 3 key */

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 3);

*itemHit = 3;

return TRUE;

break;

}

/* These key equivalents for buttons use

the command key, and are appropriate even

for use in a modal dialog with editable

text. */

case 102: /* ASCII F */

if (theEvent->modifiers & cmdKey)

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 1);

*itemHit = 1;

return TRUE;

break;

}

case 115: /* ASCII S */

if (theEvent->modifiers & cmdKey)

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 2);

*itemHit = 2;

return TRUE;

break;

}

case 116: /* ASCII T */

if (theEvent->modifiers & cmdKey)

{

FlashDialogItem(theDialog, 3);

*itemHit = 3;

return TRUE;

break;

}

default:

/* Do nothing if another key is chosen. */

return FALSE;

break;

} /* end of key code switch */

case (mouseDown):

/* You can insert your own mouse click handlers

here. ModalDialog takes care of mouse events,

but you can do special processing. For example,

ModalDialog does nothing if a mouse click occurs

inside a modal dialog but outside of a control,

but you could do something. */

return FALSE;

break;

case (mouseUp):

return FALSE;

break;

default:

/* We don't handle any other types of events, so

these get sent to ModalDialog unchanged. */

return FALSE;

break;

} /* end of switch */

} /* end of filterproc function */

/************************************************/

/* HandleDialog is a function to draw and dispose of a simple

modal dialog. It tells ModalDialog to use a filter proc to

screen events for the dialog. */

/* Input: short Dialog_ID - the resource ID */

/* Output: item number of the control that was hit to

exit ModalDialog. */

int HandleDialog(dialog_ID)

short dialog_ID;

{

int itemHit; /* returned by ModalDialog */

DialogPtr theDialog; /* The dialog we will work with */

GrafPtr oldWindow; /* Saves the previous window */

GetPort(&oldWindow); /* save current grafPort */

SetDAFont(0); /* use system font */

/* First, get the dialog from the resource and prepare

to execute ModalDialog */

theDialog = GetNewDialog(dialog_ID, (Ptr)0,

(WindowPtr)-1);

if (ResError() != noErr)

{

/* Called if GetNewDialog returns an error. You can

put your own error handler here. In this example

we are assuming that the dialog is available in

the application resource fork */

SysBeep(40);

ExitToShell();

}

ShowWindow(theDialog);

SetPort(theDialog);

FlushEvents(everyEvent, 0);

/* Modal dialog call should wait until event in

active control */

ModalDialog((ProcPtr)FProc, &itemHit);

DisposDialog(theDialog);

FlushEvents (everyEvent, 0);

SetPort(oldWindow);

/* restore drawing state */

return itemHit;

}Note: .r files were meant to be compiled with RMaker, a standalone resource compiler for old MacOS which turns text files into resources. In this case the output filename is meant to be the same as the project file name with an .RSRC suffix, where [pi symbol] was an actual pi symbol. Currently the text in the staticText item is too wide to fit my web page template without wrapping. This text must be on a single line, as the RMaker tool cannot handle multiple lines of text. It renders correctly in the PDF version.

**************************

*

* RMaker source file for

* filterProc application

*

**************************

Filterproc.[pi symbol].RSRC

RSRCRSED

Type DITL ;;Text for dialog

,1 ;;Resource number

5 ;;Number of items

Button Enabled

17 27 37 95

First \11F ;;The non-printable character is ASCII 17 (see text)

Button Enabled

17 108 37 182

Second \11S

Button Enabled

17 200 37 262

Third \11T

editText Disabled

137 86 157 222

This is editable text

staticText Enabled

61 43 115 246

This is an example of a modal dialog with command-key equivalents for buttons.

Type DLOG ;;modal dialog

,1

90 120 266 420

Visible NoGoAway

5 ;;proc id

0 ;;refCon

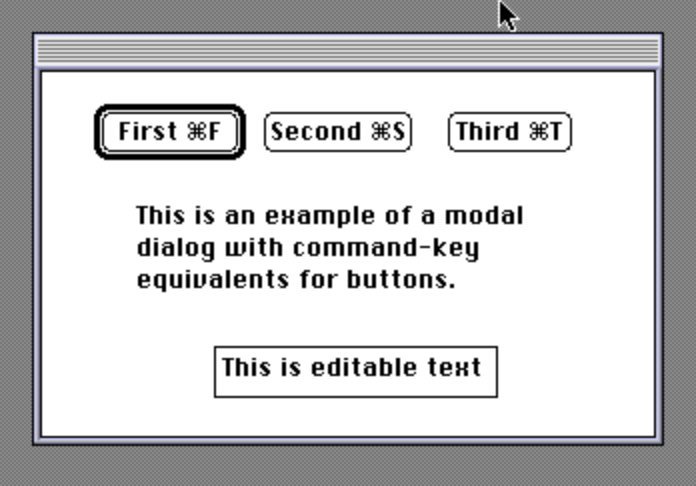

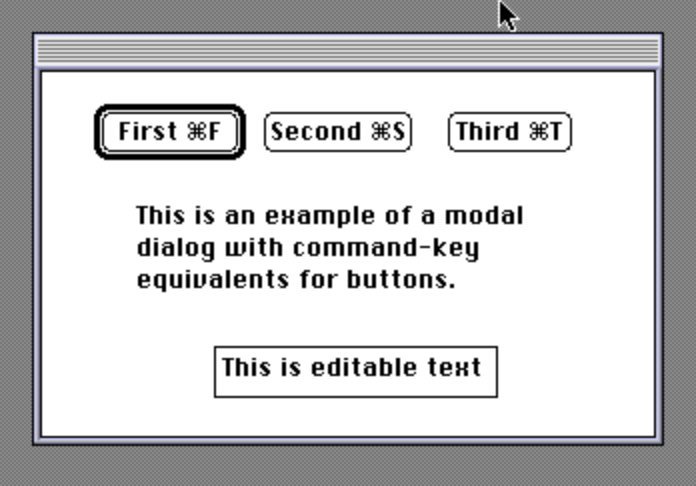

1 ;;DITLI was able to get Basilisk II running on my MacBook Air M2, following these instructions. I have not attempted to build the code, but I was able to run an archived build from a disc file image in my archive, dragging it into the shared folder. And it worked! Hitting the command keys selects the appropriate buttons. 35 years later, here’s what the application looks like: