Today is Monday, June 12th, 2017.

Summer has arrived and I have not cut the grass at our new house in Pittsfield Township, so it is almost waist-high. Walking around the yard, it feels a bit like being hip-deep in swamp water. We set up a fire ring, but we can’t use it until the grass is cut.

We have a mower, but two years ago my Dad ran it over a rock and damaged the blade. He took the blade off, put the mower away wet and completely gunked up with wet grass, and headed back to California. I took the blade to Ace Hardware in Saginaw to be sharpened, and picked up the sharpened blade, but having just started my job in Ann Arbor, which required living half of each week out of town, my time at home with the kids was very limited. I didn’t want to spend it mowing the lawn. So I didn’t get around to trying to reinstall the blade, and we wound up just paying a lawn care company to cut our lawn for a while.

A few weeks ago, I brought the mower down to the new house. I flipped over the mower to try to figure out how to reattach the blades. There are two. I don’t have the tools on hand to reattach them what with the moving in progress (the sockets are… somewhere…). It’s also not exactly clear to me how the blades go on (and the manual is… somewhere…). Meanwhile it looks like putting the mower away covered with wet grass led to a lot of rust on the blade drive shaft and the underside of the mower.

So I need to take it to a shop, which is also a thing, because I know where in Saginaw I would happily take it, but not the equivalent in Pittsfield Township. So I’ve got to find a place and take it there. It won’t fit in Grace’s car, so she can’t do it during the week. I’m also not entirely sure the mower will be fixable. Which is pretty aggravating, because it was a $400 Honda mower.

So our yard desperately needs an extreme mowing, but at this point a mower won’t even cut it and we will need to rake up and compost the very tall grass and weeds. So I might need to go over it with the rechargeable weed whacker, hacking down a small area at a time and raking up the results. We’ve also considered trying to hire a neighborhood kid, or maybe someone who is not a kid. The lawn services Grace spoke to don’t want to come out once or even a few times. They are only interested in doing business if we sign up for weekly service for several months.

On the positive side, I am continuing to feel gradually better.

Work is coming along. I’m in an “implementation slog.” I’m adding features to the firmware for the MX family instruments. I’ve done the proof-of-concept, the first partial implementation, the beta-testing, and the improved design. I’ve then taken that redesign and implemented about three-quarters of it. I’ve solved the interesting problems and the rest is mostly implementing a bunch of code that is, by design, somewhat redundant and standardized in structure.

My prototype design was more complex, using a forest of C++ classes, where I had to subclass objects for custom behavior and hook them up to each other in containers using an observer pattern. But it was hard to read, and would have been much harder to maintain and extend. Sometimes the tough part of a software development job is solving a design problem. Sometimes the tough part is understanding and fixing a tricky bug. And sometimes the tough part is maintaining your concentration and making steady progress while implementing a large, but deliberately simple and clear, and so boring, piece of code.

This weekend I made two trips up to Saginaw to continue the sorting and packing. Summer arrived with a vengeance and it was hot. Summer road construction has also arrived and the Michigan state flower — the orange and white plastic road construction barrel — is blooming everywhere along my route. On Saturday, it took me three hours to make the drive to Saginaw, which normally takes about 100 minutes. So I sat pretty much stopped in traffic for an extra hour and twenty minutes, trying not to grind my teeth. I would have done deep breathing, but in the miasma of extra ozone, soot, dust, and pollen, that is not advisable.

The rooms I was working on — the office and studio — are on the highest level of the house, built partially into the attic. The net effect is that it was very hot up there. So I spent Saturday and Sunday afternoons into the evenings drinking quart after quart of water and sorting and packing little bits of stuff that accumulated in my office over the last seven years.

I threw away a lot, but I’ve learned that can be very important to keep certain kinds of paperwork, particularly anything having to do with my unemployment benefits, and there was a lot of that. When you’re unemployed, the paperwork is pretty much a full-time job, especially when you include the work search records. A good chunk of my notes could go, especially the notes having to do with jobs past. There were many notebooks full. When doing my software development work, I jot down design ideas, little to-do lists, and notes from meetings, constantly. Even if it is only amounts to a page or two a day, it adds up over the months and years. Looking back at those old notebooks, I find myself slightly stunned by how much work I did, just plugging away steadily at those jobs.

What really slows me down is the detritus of half a million little personal projects. There are homeschool projects, electronics projects, music projects, podcast projects, writing projects about C programming, writing projects about electronics, and documents and notes for my adjunct teaching gig. There are pictures and bits of family history. Much of this I don’t actually want to throw away. The notes can go, at least once they serve their actual purpose and I integrate them into a writing project. I am hesitant to actually throw away antique photographs.

So the best I could do in some cases was to sort the stuff well enough to pack it, with an eye towards sorting it further at the new house. So I’m committing myself to spending even more time. But at least there is space in the new house to actually get it sorted. And it’s not sweltering in our new basement.

I also brought my desks, which are sanded and stained wood-veneer doors (probably built on a plastic foam core), placed on top of plastic sawhorses. The doors barely fit in the car. I have to push them between the two front seats and hope I don’t need to brake hard. And I brought a number of delicate items that needed to be hand-carried. Among these are some ceramics my mother made, back when she went by her maiden name. There are ceramic egrets with long, graceful necks. The necks are so fragile that I don’t even want to try to put them in boxes. The necks can’t support their own weight. So I carried them wrapped partially in bubble wrap and placed right on the passenger seat, strapped gently to the seat, the necks hanging over the edge. I hoped for the best. They made it. They’ve survived for over fifty years and I’m hoping not to be the one who breaks them.

On the one hand, I’m hoping not to burden my kids with a hoarder-house, a home piled with what may seem like, to them, a lot of garbage. On the other hand, I’d like them to have some sort of organized legacy — my library, my mementos, an archive of items left to me by my family of origin. And I want to leave them a trove of items from their own childhoods — what records are worth keeping of the places they lived, the things they did. That trove is inevitably part-digital. How to make sense of all that, and try to help it survive to another generation, is a big subject. But I think a strategy is starting to come into shape, and the new house can help me work on that — steadily, a little bit at a time.

Anyway, our house-emptying project continues. I’m doing as much as I can bear to. We are not at all happy with our progress. We wanted to be finished by now. But I try to enjoy the small victories. When I left Saginaw on Sunday, the office, studio, and bathroom were completely empty of everything, except for a pile of framed and loose posters. The posters along with Grace’s framed posters and pictures will probably require a carload of their own. And I’m really not sure where they will go, in the new house. But we’re getting stuff done.

I have my desks set up in the new house and they look good there. The room they are in is a basement room, with no windows, but yet it is much less claustrophobia-inducing, to sit at them there, than it was to sit facing the sloped attic walls in the old office.

Speaking of minor victories, I want to take a moment to note that I am all caught up on the New Yorker. It’s taken me months, but I have worked my way through the backlog of issues and completed the most recent one. For the first time in forever, I don’t have a New Yorker to read! In a burst of optimism I might hope that I can actually, now, keep up, reading each one when it arrives, and completing it before the next one arrives. But let’s not get too far into crazy talk.

Now, if I could only get on top of the pile of back issues of the New York Review of Books… but hey, small victories!

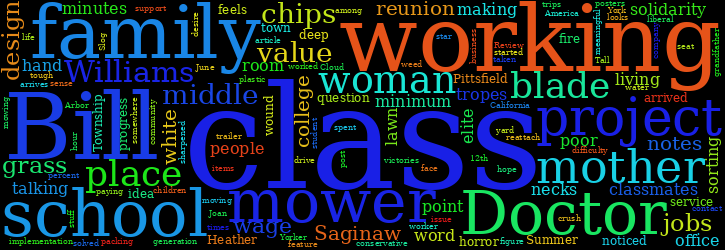

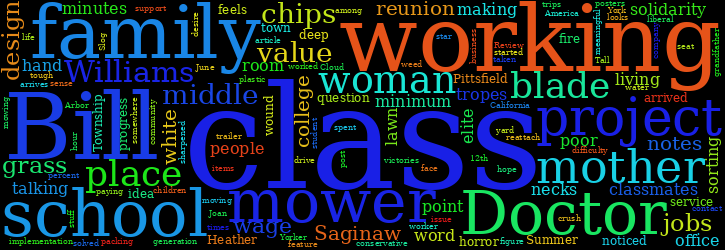

There are a lot of recent books that take on the 2016 election, from one perspective or another, and I’ve become wise enough to realize that although I might enjoy starting all of them, I am not very likely to finish any of them. But I did pick up one book that I think I can probably finish, a thin book called White Working Class: Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America by Joan C. Williams.

I have read and watched Williams in a few recent interviews, and liked what she had to say enough to try reading her book. It seems like she has some insight, although I am not sure how much, and some advice, although I’m not sure how useful it is.

My first difficulty stems from trying to figure out what class I fit into. This has been an issue my whole life. My mother’s parents were upper middle-class, educated, descended from bankers, with both Revolutionary War and Civil War soldiers in my family tree. My maternal grandmother was college-educated, a schoolteacher. My maternal grandfather worked as a chemist for Welch’s, the grape juice company. He had to move his family repeatedly for work, and wound up moving his family to North East, Pennsylvania and working at the Welch’s factory in Westfield, New York, actually leaving my mother in California while she finished high school. My mother, after my parents divorced, followed them, meaning that my family started out split across the country. My mother found herself raising two boys while living in a trailer. With my grandfather’s financial help, my brother and I went, for a few years, to an elite private school, among the children of doctors and lawyers, while also living in a trailer.

I did not fit in well there, or in high school. Because of my mother’s background, I don’t think she ever felt at home among the working-class residents of our trailer park. She worked as an Occupational Therapist at Hamot Community Mental Health. She was culturally middle-class or even upper middle-class, but her financial circumstances as a single mother made her financially lower middle-class or working poor. She had few friends, although I think she did find a sense of community in the First Presbyterian Church of North East, eventually becoming a deacon there.

I was raised partially by my grandparents, but my grandfather died when I was nine years old, and so I think my education in how to be middle-class was somewhat stunted. My mother remarried, to a man who was a World War II veteran and assembled motorized wheels at General Electric. He was firmly of the working class, and a lot of his value system rubbed off on me. In high school, I had difficulty fitting in, and as a scholarship student in college, also never really felt at home. The real values I absorbed seem mostly to center around the primacy of work and a deep fear of being impoverished. And so for decades I’ve put work ahead of pretty much everything.

I had never really realized what our more elite educational institutions were for, besides the secondary mission of education — they were for networking and acculturation. They exist to reproduce class in the next generation. Cash-poor while in college, I never could take the overseas trips or ski trips or other added-cost opportunities. I studied, very unevenly, pursued my interests like audio production and writing, drank only moderately, and tried to learn the basic relationship skills I had mostly failed to learn in high school (see “intellectually advanced, socially retarded.”) Failing to network, I never really learned to use my “PME” (professional managerial elite, to use Joan Williams’ term) contacts to find work. It also means that I feel almost as out-of-place at a college reunion as I think I would feel at a high school reunion.

My current income brings me within spitting distance of the class that Williams calls the PME, and which I’ve also seen called the “cosmopolitan elite,” and yet not only do I not identify with those folks, I tend to avoid things that would signal my solidarity with them. I don’t like to fly — it is ostentatious and carbon-wasteful. I’ve done a little management, but I am very ambivalent about doing anything that feels like “ladder-climbing” away from the kind of work where I design and build things. I left my community of origin, expressing a middle-class value to flee, not stay in an economically un-promising place, but have since tried (and failed) to find an economically un-promising place and establish roots there, and try to help build that place up. I now find that I feel like an outcast in the city I spent twenty years living in, Ann Arbor, because it has priced me out, and with a large family, to the liberals DINKs and one-child families, my family might as well be Amish, arriving at local restaurants in a horse and buggy. And so on.

I think Williams has some good recommendations, about how we need to think deeper about, for example, why poor working people don’t simply move to find better work. That’s a facile and deeply offensive conservative talking point and Williams demolishes it, and rightfully so. That kind of mobility scatters and demolishes traditional family support structures, and the brokenness that forced migration for employment causes can persist for generations, as I well know.

While I am finding the book to be worth reading so far, I also agree with this review in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

The book is not about the working class in any meaningful sense. Its treatment of race is, at best, fleeting. Regarding the former, Williams arrives at a definition of the working class that is neither traditional and coherent nor usefully innovative. She expels the poor, wage earning or not, from the ranks of the working class and shuts the very rich out of the ranks of those holding it back. Income alone, not the more meaningful measure of wealth, defines her answer to the question “Who Is the Working Class?” The bottom third and top 20 percent are excluded, with an exception made for those making more but not having college degrees. The result is a “class” defined by making $41,005 to $131,962 annually (median: $75,144), and by holding values alternately seen as understandable or wonderful.

In one notable passage, the author talks about the difficulty of making small talk at a high school reunion, particularly how, to a working-class person, the question “so, what do you do?” can induce rage in a man who sells toilets. In an interview, Williams suggested that a better opening conversational gambit, when talking to a working-class person, might be “how about that (whichever) sports team?”

She’s trying to avoid confrontational topics, and that seems like a good idea, but the idea of having to actively study sports, a subject I have no interest in at all, in order to communicate with my old classmates at a high school reunion, still seems not just condescending but misguided. As the victim of constant bullying, I have mostly solved the dilemma of how to communicate with them by never attending a high school reunion (and a couple of years back I missed my thirtieth), and only very occasionally, and briefly, returning to the towns I grew up in.

With my family there all dead, the only reason in 2017 I might go back to Erie, PA is to take my children to visit their ancestors’ graves. And because my children haven’t grown up anywhere near there, the question of where I myself should be buried, or have my ashes buried, as a vexing one; I would like my marker to be in a family plot, to honor my mother’s family, but if I would not condescend to visit those places while I was alive, why would I want to “live” there after my death?

From what I can tell on Facebook, ignorant bullies remain bullies, well into middle age. And the single most salient feature that I can discern in the posts of my working-class high school classmates is their lack of solidarity. Not solidarity with me — I mean, I left and was successful, right? I’d say “fuck that guy” — but even solidarity with themselves. If I post an article about how workers earning minimum wage cannot pay for a two-bedroom apartment in any city in America now, my old classmates, who might be supervisors or floor managers in chain stores now, talk entirely about how it is the fault of the workers. Never mind that if seventy-five percent of the jobs available in a given town pay minimum wage, then seventy-five percent of the people who live there have to take one of those jobs, if they want a job. But to my classmates, it’s always, and entirely, about how certain people refuse to work harder and better themselves, like they supposedly did.

Their sympathies lie entirely with, and their expressed aspirations fit entirely within the values of, the business owners. There’s no room to talk about how, if the minimum wage had kept up with inflation since 1968, it would be about $4 an hour higher than it is today; the 1968 minimum wage, adjusted to 2015 dollars, would be $10.90. My classmates are talking about minimum wage jobs as if they were starter jobs for high-school students working part-time for spending money. But that has not been true for many years.

And they are Trump voters, for the most part. Not just Trump voters, but people who still support him and are actively defending him today. Try to debate, and post a link to an article — they will run it through a web site which rates the reliability of the source based on how allegedly conservative or liberal it is (liberal bad, conservative good) and tell me they can’t accept the argument because The New York Times is bad, but Breitbart is good. There’s no getting to shared facts — every fact is suspect. And to try to talk with them about values is, basically, to invite a torrent of repeated Fox News talking points.

So, and this is a serious question — what do we have to talk about, which would be meaningful to both of us? What could we say to each other that wasn’t just born of uncomfortable, condescending politeness on both our parts?

While I may be at least temporarily close, financially, to that “PME,” what with paying two mortgages and a barrage of medical bills I sure don’t feel like I’m not part of the precariat. And it’s not at all clear to me that I’ll be able to pay off the house before I have to retire, or how long I can do this kind of work before some combination of ageism and actual cognitive decline starts to make it impossible to get hired again.

Would their answer to my anxieties be “work harder in order to better yourself?”

I got off on a bad footing with the first episode of Series Ten. Amusingly, the very first word spoken in the episode is “Potts.” We meet Bill Potts, a young food-service worker and black lesbian. She works at the University where the Doctor just happens to lecture, and attends his lectures. The Doctor summons her to a meeting, offering her an opportunity for special tutoring, despite the fact that she is not even enrolled in the University.

Immediately we get a very muddled set of values. In a rapid-fire speech, Bill explains her interactions with a white woman at the school. Bill noticed this woman, apparently, because she noticed the Doctor noticing her. Bill then wanted either to remove the source of the Doctor’s distraction, or found herself attracted to the woman because the Doctor was attracted to her — I’m not really clear on this:

“Okay, so my first day here, in the canteen, I was on chips. There was this girl. Student. Beautiful. Like a model, only with talking and thinking. She looked at you and you perved. Every time, automatic, like physics. Eye contact, perversion. So I gave her extra chips. Every time, extra chips. Like a reward for all the perversion. Every day, got myself on chips, rewarded her. Then finally, finally, she looked at me, like she’d noticed, actually noticed, all the extra chips. Do you know what I realised? She was fat. I’d fatted her. But that’s life, innit? Beauty or chips. I like chips. So did she. So that’s okay.”

I’m not entirely sure what to make of this, but it seems like Bill lost interest in the woman after she became fat. Or maybe she was pleased to have “fatted” her, because she now was not in competition with her for the Doctor’s attention? And a few minutes into the show, in a montage of Bill’s life at school, we see her wink at an overweight woman as she shovels extra fries onto her plate. Whatever the intent, this comes off as the show fat-shaming that actress for laughs, and she doesn’t even get a speaking role. I’m surprised she isn’t listed in the credits as “Butt of Fat Joke.”

So I was interested, but then I was also a little puzzled and dismayed, after only the first few minutes. And then we got a strange, ineptly produced take on the myth of Echo and Narcissus. Bill meets a young woman in a club, makes eye contact, and falls head-over-heels in love. The woman has a strange feature in the iris of one eye: a small star-shaped patch. (She looks at Bill and Bill literally sees stars; the woman has stars in her eyes; choose your own heavy-handed metaphor.)

Knowing next to nothing about her, Bill has such an intense crush that after they speak a few words to each other, Heather asks “Please. You can say no. Would you come with me? Can I show you something?” And Bill practically shouts “God! Yes!” in a way that I find unnerving. Her desperate desire for love and her tendency to form fast crushes seems to be very out-of-sync with the stoic, cynical young woman who is accustomed to disappointment.

Bill’s crush, Heather, is in scenes that must have been photographed across a couple of different days of shooting. Her hair changes, and her makeup changes. I’m just a touch face-blind, and her face changed so much that I wasn’t sure she wasn’t played by a different actress in some scenes. And after this confusion, the episode turns into a very rapid-fire pastiche of horror tropes — traditionally misogynistic horror tropes. Heather liked Bill, but before long she was, in monstrous form, chasing Bill with fingernails extended like claws, screeching like a banshee, popping out of puddles like Meg Mucklebones in the movie Legend:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IxjYJayuWoA

Unlike Meg, who desires flattery, Heather, once dissolved into a puddle by her desires, can only echo the things Bill says. I was reminded quite uncomfortably that homosexuality has been historically been considered a form of narcissism, and linked to a failure to achieve the ability to form mature relationships. And here we have Bill, with a tremendous sudden crush, being pursued by a watery hag-creature that echoes her words and reflects back her own face. Contrast it with an episode it reminds me of, “The Curse of the Black Spot,” which invokes horror tropes as well as the mythology of the Sirens, but more intelligently and deliberately, and was better in just about every respect.

I wrote about this on Facebook, and long and ultimately pointless argument ensued, with people arguing that I was over-interpreting and seeing things that weren’t there. I wound up watching the episode twice more. Maybe I was over-interpreting, but even on the third viewing I still found this episode disjointed and disappointing. I think the show in general still has a tendency to slip far too readily into very conventional horror tropes, and does so a bit unthinkingly, even when those tropes are associated strongly with sexism and misogyny.

I expected better from this new season. For the most part, the episodes that followed haven’t been as disjointed, but they haven’t been that good. “Smile” was not bad, but “Thin Ice” seemed very derivative of “The Beast Below.” “Knock Knock” seemed very derivative of “The Doctor, the Widow, and the Wardrobe.”

The three-parter “Extremis,” “The Period at the End of the World,” and “The Lie of the Land” — well, they’ve had some nice moments but none of them seem to really work well enough to keep me from getting distracted by the gaping plot holes. Last night’s show “The Empress of Mars” was not bad, but again, not great, either — not one of these season’s episodes have lived up to “Blink” or “The Girl in the Fireplace” or Capaldi’s “Heaven Sent.”

The show has introduced a storyline involving Missy, but has spent very little time actually setting it up. The series has only three episodes left to turn around, or it will be remembered as a mediocre series. That would be a shame, as Peter Capaldi makes a pretty good Doctor. I just feel that he wasn’t given the best material, especially not this season. It all feels to me like the show is running on recycled ideas at this point. I hope it gets better, but I fear we’ll have to wait for a future series for that.

Pittsfield Township, Michigan

June 12th and 13th, 2017