I have a slightly uneasy, never-quite-resolved relationship with certain books. Call it some kind of a learned elitism if you will, or classist sensibility, or overdeveloped Protestant-work-ethic aversion to fun. I like reading them, at the same time that I feel slightly guilty for doing so — you’ve heard them called “guilty pleasures.” As I read them I’m aware of their flaws and aware of just how cynically they were written — but then that leads to all kinds of wandering thoughts about whether any book, any story, or any essay is ever written entirely un-cynically, and how is it great books get written, anyway? Bleak House was written so that Dickens could get paid by the word, and published in 20 installments. Bleak House is fascinating but it is standing unloved on a shelf with my bookmark stuck firmly somewhere prior to page 100, and it’s been sitting there for so long it might as well be welded shut and the bookmark glued in place, while I’ve plowed through dozens of lesser books in the meanwhile.

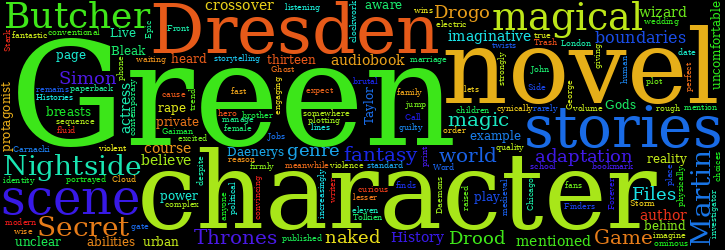

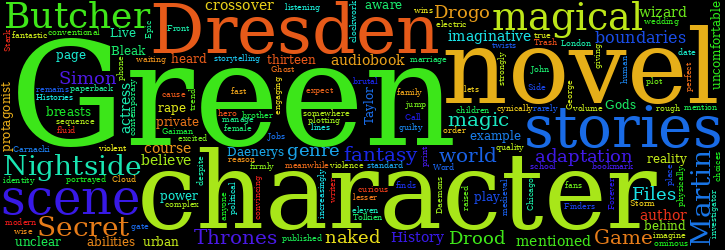

On Steve Eley’s Escape Pod podcast, a few years ago — oops, I guess that was almost seven years ago — I heard a review of Simon R. Green’s first few Nightside books, and they sounded fun. These are fundamentally fantasy novels, although you could also call them “horror,” or “gothic,” or “dark fantasy,” or “urban fantasy,” or even “magical realism.” I’m not going to jump into a big controversy over the boundaries of genres, but let’s just say that the world portrayed is modern — there are computers, cars, and phones — but the location is fantastic.

The books are mostly set in the Nightside, a sort of London underworld, a bit like the “London Below” in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere. The Nightside is a real place where magic works, a small city in perpetual night, and it is somehow more real than reality — a sort of dimensional crossroads that underlies and intertwines ours. Our hero is John Taylor, a private eye (what else?) with magical ancestry — he is the son of Lilith — and magical powers with unclear boundaries. These unclear boundaries are precisely what makes the series fun and imaginative, and also frustrating.

The novels are short, and fun — Green really lets his imagination off the leash. Things get very crazy very fast. Green mines the cultural tropes of gods, demons, Arthurian legend, and popular culture, and owes more than a little to Gaiman’s books like American Gods as he does so. Merlin himself shows up, and he’s not the cuddly, bumbling, befuddled wizard of Disney’s The Sword in the Stone. It gets dark fast. And so I was a bit hooked; I’ve read the first eleven, and the twelfth, allegedly the last, is out in hardcover now, and as usual I’m waiting for the paperback.

So the books are fun, grotesque, dark, and very, very entertaining. What’s not to like? Well, there are a few things. The rules of the game we’re playing are unclear. It’s pretty standard for Green to bring in a character that hasn’t been mentioned in book after book, but suddenly gets mentioned, and all of a sudden everyone seems to have always known about this character and how dangerous he or she is. I should mention that this problem isn’t limited to this particular series, and of course it’s not limited to Green’s work.

So John Taylor always wins, and wins through the use of his Gift, with a capital G — his second sight, his third eye, his ability to see reality at a deeper level. But he can’t just see underlying cause and effect — he can cause effects. So he removes the bullets from guns, either literally or metaphorically. Taylor turns on his magical powers and then it is “the easiest thing in the world” to defeat his enemy. Green uses that phrase over and over, and so it is best not to read the books back-to-back, because if you do, the formula and outline will stand out pretty clearly. And so in this regard a series that feels very imaginative and seems defiant and edgy is, writing-wise, about as conservative and conventional as you can possibly imagine.

So, I don’t want to bash Green too hard — these novels are really fun and imaginative. But at the same time I’ll breathe a little sigh of relief when he finishes this series, and I doubt I’ll be re-reading it.

So partway through Green’s Nightside books he started another series — the Secret Histories. These are crossover spy novels rather than crossover private investigator novels, although as the series goes on the spy aspect is increasingly irrelevant. The “Secret History” concept comes into play because it’s the conspiracy theory view of history, particularly the history of the powerful Drood family, and the protagonist Eddie Drood hides his secret identity behind another secret identity, that of super-spy Shaman Bond. And so the books have puntastic titles like Daemons are Forever and Live and Let Drood. These novels are much longer and more complex than the Nightside books, and there are six of them to date. I’ve read five. Again, I’m waiting for the most recent, Live and Let Drood, to come out in paperback.

The longer format suits Green — the plots can get more convoluted and more fantastic, and he can devote more pages to high-tech weaponry and mayhem and magic, including the Drood family’s amazing magical armor. But of course the books tend to have the same sort of deus-ex-machina plotting that will get our hero into any crisis. So the stakes have to be raised to keep the reader’s interest in the characters — raised higher, and higher, and the effect can be a little mind-numbing. But again, these books are a lot of fun, but again, pace yourself and don’t expect really convincing plotting. As you might expect of an author juggling several series at once, there is crossover between the series — I believe these are all basically set in the same universe as his Deathstalker series, which I have not read. But the crossover with the Nightside is not as deep or interesting as one might have hoped.

There’s another series I’ve tried — Green’s Ghost Finders series. I was very excited to see this series start because I am a big fan of William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki stories, and I’ve collected some Carnacki stories, pastiches, and parodies by other authors. Unfortunately Green seems to set the wrong tone right out of the gate — the stories seem much too violent, and much too dark, turning the dial up to eleven on page one, and they don’t manage the dramatic tension properly at all. I found the characters unlikable. The first book was a disaster, but I decided to soldier on and try the second one, and was also disappointed, so I won’t read any more books in this series.

Green is prolific. He’s clearly subscribed to the hard-working, cranking-them-out-on-a-schedule school of writing, along the lines of Piers Anthony. As I’ve never published a novel, I feel a bit uncomfortable criticizing that school of writing, and I’ve seen some authors crank out volumes of work that are almost uniformly very successful — I put Alastair Reynolds and Iain M. Banks in this category. Still, I’m not convinced that quantity is the guarantee of quality. I’d like to read some of Green’s other standalone work — I’m curious about Shadows Fall, for example — but I’m not eager to jump into another one of his series, because given my obsessive tendencies, if it is any good at all, I’ll probably feel compelled to read it until the end. Which brings me to another writer in the “urban fantasy” genre and another series…

I noticed that Subterranean Press will be releasing Side Jobs, a volume of Jim Butcher’s stories about Harry Dresden, his wizard protagonist. This made me curious about The Dresden Files novels, so I picked up Jim Butcher’s Storm Front. Dresden is an urban private investigator who is also a wizard, in contemporary Chicago. Most of the interesting conflict in the stories concerns Dresden’s attempts to reconcile his very impressive magical abilities with his very unimpressive abilities to navigate his dreary, somewhat impoverished daily life in contemporary Chicago. Magic and reality coexist uneasily in Dresden’s world. For example, his magical aura has a tendency to short out any devices containing electric circuits, from light bulbs to electric fans to car engines, so he lives in a boarding-house basement, lit by oil lamps and candles and heated with a fireplace, and he can barely keep his ancient Volkswagen Beetle running.

It is this sort of limitation that makes the stories themselves more human and engaging. Butcher’s world of magic has some distinct limits — for example, Dresden is answerable to a White Council of wizards, who look strongly askance at killing anyone with magic, while the bad guys often don’t labor under such constraints. Dresden also is himself the source of the energy behind his magic, and so he can pretty easily over-tax himself. And physically, he’s quite human and breakable. Dresden’s enemies chew him up and spit him out hard. It always seems a bit hard to believe that Dresden is able to walk, much less fight, in time to star in the next book, but we’re meant to understand that his magical abilities come with enhanced healing power.)

Butcher doesn’t seem to have the knobs controlling ominous threat, violence, and punishment set quite right for maximally effective storytelling, but he’s definitely getting somewhere. I found the first book, about the local mafia and a magical murder, to be a little rough — the writing not so fluid, the plot twists a little predictable. But still, there was something imaginative enough about his protagonist to keep me going, and I’m now reading the fourth. Butcher’s writing is becoming more fluid and free, and to my delight he seems to feel even freer to sprinkle in wordplay and bad puns. In the third book he manages to introduce another character who is very compelling, Michael, an actual knight of God. There are fourteen (wow!) novels so far, and so this series is no small commitment, but I can stop whenever I want. At least, that’s what I keep telling myself.

I can’t really recommend blowing through a whole series like this in order, without allowing for some palate-cleansers in between. Reading this sort of series back-to-back is, it seems to me, kind of like watching a TV show on DVD by watching all the episodes back-to-back — when you do so, their similarity becomes blatant, and the seams become much more visible. It’s better to take time off to forget the faults of the last one, and doing so will let you better enjoy the next one.

That said, if Butcher’s writing continues to improve as it has been improving in the first three, I might not be able to help myself. The most recent few might be very good if the trend holds true. Just by way of comparison, I’m not sure I can detect any upward trend in the quality of Green’s books, at least those that I’ve read, and as I mentioned, his Ghost Finders books to date provide a lot of evidence to the contrary and scream “hack!”

When Butcher’s story collection Side Jobs is released, I plan to buy it and read it. I suspect very strongly that what I’ll find is that Butcher is better at writing short stories than he is novels, and that I will then come to see his Dresden files novels as short stories inflated to novel length for commercial reasons. I’m not sure how true that is, but I’ve been reading J. G. Ballard’s short stories, and in his introduction he says that he finds it interesting that there are no perfect novels, but many perfect short stories, and I can’t really disagree.

In between the last couple of Secret History and Dresden Files I’ve become increasingly aware of another phenomenon exciting geeks world-wide, and threatening to bust the boundaries of several different genres — George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels.

So for various reasons, likely having to do with four young children, I am probably the last fantasy fan to read A Game of Thrones. I’m embarrassed to admit that I did not even know who George R. R. Martin really was until recently, when I connected up the bushy-bearded Martin of Game of Thrones fame with the author of the short stories “Sandkings” and “The Way of Cross and Dragon” that I read in Omni magazine, back in the day.

Anyway, I haven’t finished A Game of Thrones despite the fact that I purchased it first as a 28-disc audiobook. I rarely buy audiobooks, but decided that this might give me a better taste of his language, and I was right — it’s terrific this way, although I don’t often get to focus on listening — add in those four young children, a constantly ringing phone, and constant knocks on our door, to the point where the only time I’ve heard any of it uninterrupted is while driving, and since I work from home, I don’t drive regularly. Anyway. The audiobook narrator is Roy Dotrice, and he does a great job with the characters, even the female characters, and that’s a huge help, because if there is one thing this story has no shortage of, it’s characters.

But of course I had to pick up a print copy too, so I can go back and re-read particular bits in print, and see how the names are spelled, and then we don’t have cable, and so I’ve never seen the HBO adaptation, but I bought the season one DVDs and now I’ve watched the first episode, with my wife, after both listening to and reading the first part of the book, and so I’m ready to share Impressions and Pontificate.

So Martin’s prose is excellent — very engaging, beautiful, profane, dark, sardonic, and brutal. The genre is, more-or-less, “high” fantasy. But except for superficial similarities, don’t think Tolkien; Tolkien’s characters are wise and witty, noble and regal, often aloof and magical. Martin has pretty much turned that upside-down and his characters are Shakespearean — Falstaffian, Calibanesque, or tragic. The setting is medieval, roughly along the lines of the War of the Roses, and there is clearly some magic at play, although so far it is mostly veiled. But so far to me it is Martin’s sentences are just delicious. I rarely get this excited about genre writing, but the dark humor and wit and sadness and even love on display in just about every bit of dialogue is really rewarding. It is a reminder that writers in their later career can still be really formidable and in fact may be doing their best work.

The HBO adaptation makes very interesting choices, and I want to talk a little bit about those choices because this is, I believe, where the “fun trash” label again applies. First, having seen only episode one, there’s a lot to be said about how well they’ve done it. The title sequence itself is a small masterpiece — clockwork castles and villages rise from a map, giving new meaning to the idea of political machinations, and overseen by an ominous sun, like a burning eye inside a knife-bladed armillary sphere, suggesting that the clockwork is driven by the unstoppable march of the seasons.

Beyond that, there’s just no getting around the fact that the visual adaptation of the story must be brutal; there are beheadings almost immediately out of the gate. The sets and costumes are gorgeous. But it’s the use of nudity in the TV show that is a little puzzling, and twists the storytelling towards the more prurient. In an early scene, Catelyn Tully and Lord Eddard Stark are in bed together — having just finished a vigorous coupling. In the book, she is stark naked (haha) in this scene, and remains so even as she lets in an adviser, who brings her a secret message from her sister. He covers his eyes, and she tells him that he needn’t bother, as he’s delivered all her children and so she has no more secrets left to keep from him. It’s an establishing scene, and helps portray her character as fierce and extremely pragmatic. In the TV show’s version of this scene, she remains entirely covered, and so the scene fails to convey what the scene in the book conveys about her character. I imagine that maybe the older actress wasn’t willing to do the scene nude, but there are downstream storytelling consequences that must be accounted for. Also, in the book, Eddard Stark is just as naked as Catelyn, and I can’t believe female fans wouldn’t have enjoyed a good look at Sean Bean, but he remains firmly covered as well.

Meanwhile, Daenerys Targaryen gets a thorough inspection by her cruel older brother Viserys. In the book she is clothed — he pinches her nipple “through the rough fabric of her tunic” as he examines her “budding breasts,” wondering whether they are large enough to please Khal Drogo. Later he will order her to “let him see that you have breasts — Gods know you have little enough as it is.” But in the TV show, she is naked, and clearly older (the actress was about 23). Her body is luxurious, a very nicely upholstered sport-utility body with enticing breasts and buttocks. Neither an ass-man nor tit-man would have the slightest reason for complaint — Lord knows, I would be lying if I said that I minded looking at her myself — but I couldn’t help but wonder why I was looking at her. Because in the book, Daenerys is thirteen years old.

Her brother argues that she is old enough to marry, since she has “had her blood.” Of course I’m not suggesting that HBO should have cast an underage actress in this role. I don’t think that would have been necessary, to maintain fidelity with the book. The sequence, even the bathing sequence, could easily have been shot without displaying anyone’s breasts or buttocks, while also giving it both a cruel and erotic edge, as it was written. But that would have required the producers to show a little more courage.

Instead, it seems like the character was made older, because the producers were not willing to claim that the character was thirteen, and they wanted to show the character naked. A thirteen-year-old in an arranged marriage is not acceptable to our modern standards, but why should that mean that a thirteen-year-old can’t be shown in a vaguely-medieval world which has much in common with our own historical periods in which such a marriage was common? It’s convenient that aging the character allows an older actress to play the part, which coincidentally allows her to appear naked. This is puzzling, and it can only be accounted for by the combination of cowardice and prurience.

Some of the changes are more subtle. In the show, violence is OK; rape can be shown, but not explicitly — but apparently the uncomfortable combination of rape and seduction is beyond the pale. In the book, when Khal Drogo takes Daenerys to bed on her wedding night, although she is terrified and uncomfortable, Drogo is actually extremely gentle with her. And despite her misgivings she finds herself aroused, and responding physically. And so she ultimately accepts his advances.

Has she accepted the necessity of her brother’s agenda? Is this a matter of cynical political expedience? Her motivations are not entirely clear to me, but she actually states her consent out loud, saying “yes,” and placing Drogo’s finger in her vagina.

But in the TV show, Dhal Drogo pushes her down and takes her unceremoniously from behind, like the violent rapes we saw in the wedding feast scenes (which, incidentally, seemed to me to be portrayed exactly as written) — and the scene ends. So you can show a rape, but apparently you can’t imply that Daenerys, on her wedding night, after an arranged marriage, might through her own decisions turn the scene into a scene of consent. And so, in this way, and many other ways, the adaptation flees from convincing complexity towards trashy simplicity.

I’ll keep reading and listening and watching, and see where it goes, but from what I’ve been told, the adaptation of the second book has embraced trashiness even more enthusiastically, and so I’m not sure that I’ll want to bother. It seems to me that HBO went quite a long way towards trusting their audience with a complex and subtle story — but only so far, and then no farther. And so the brilliant gold of Martin’s novel has been transmuted into something lesser. It’s less in many ways: less intense, less thought-provoking, but more conventional — and trashier.

This list does not include books, chapters of books, or other works that I only mentioned briefly in the text above.

Saginaw, Michigan

August 27, 2012